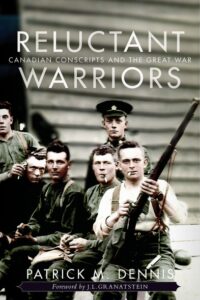

Patrick M. Dennis, Reluctant Warriors – Canadian Conscripts and the Great War (Canadian Studies in Military History: UBC Press in association with the Canadian War Museum, 2017).

~ ~ ~

Patrick M. Dennis’ Reluctant Warriors: Canadian Conscripts and the Great War, another compelling entry in the UBC Press/Canadian War Museum Studies in Canadian Military History series, is a topical and long overdue examination of a fascinating chapter of Canada’s Great War experience.

The central tenant of the book is that the Canadian Corps’ war-winning role in the Hundred Days campaign would not have been possible without conscripts. Moreover, those conscripts excelled in combat and were full and worthy partners in the acclaim won by the volunteer veterans of the illustrious Corps. The wider target of the work is Canadian historiography’s perceived denigration of this conscript contribution. Ultimately, Reluctant Warriors does a fine job of asserting the operational effectiveness and importance of conscripts, but neglects to tackle why the so-called myths surrounding them have proved so resonant.

Just how persistent are the myths that conscripts did not play an important role in Canada’s Great War? Even the website of the Canadian War Museum asserts: “Conscription would have minimal impact on Canada’s war effort. By the Armistice in November 1918, only 48,000 conscripts had been sent overseas, half of which ultimately served at the front. More than 50,000 more conscripts remained in Canada.” Persistent indeed.

And how are these assertions refuted? In Reluctant Warriors, a background section is followed by a much longer series of chronological accounts of infantry operations during the Hundred Days. Throughout, the author has unearthed – and humanized – numerous individual conscripts. We meet dozens of these young men, learn where they came from, view a number of affecting personal portraits, and review the precise manner of their deaths.

The work has immense emotional resonance, a welcome change from the detachment so common to operational history, buttressed by the author’s personal connection to the story: four of his relatives, all conscripts, served in the Hundred Days – three were killed in action and the other severely wounded.

Certainly, the contribution of conscripts has long been downplayed in historical studies, a trend that began, significantly, with Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Currie. Until Reluctant Warriors, no one had really tested the negative assumptions about conscripts first pronounced by Canada’s most famous general. But the myths surrounding conscripts are much more than another example of military history being written by professional senior officers. Most historians did not care to look deeply into conscription because it was plainly about division and its enormous cost.

Evidence of that division is largely absent from Reluctant Warriors. In the introduction, we learn that “to gain a better appreciation of how ordinary citizen-soldiers came to find themselves at war without their consent, it will also be necessary to consider the essential political, military, and social factors that put them there.” (p. 6) Regrettably, Reluctant Warriors does not actually do so. In fact, in the conclusion, the work alternately declares that to objectively examine the issue of whether or not conscription was a military necessary, “one must first set aside the fact that conscription was an extremely contentious political and cultural issue, one that dangerously divided the young nation as never before.” (p. 227) Politics and operations cannot be so easily divorced in this case, particularly since it was political expediency that begat and sustained the same myths that Reluctant Warriors is devoted to tearing down. Tellingly, conscription is seldom described as part of a “crisis” in the work. The associated canard, the claim that French Canadians did not volunteer and were therefore to be blamed for forcing the country to resort to compulsory service, has to be confronted, especially in light of the vital combat role played by conscripts from all parts of the country. In Reluctant Warriors, there is no sign of the central “us versus them” dichotomy that underlies everything to do with conscription.

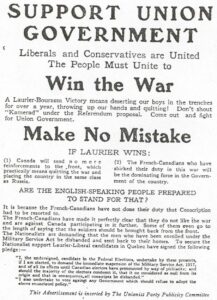

Of course, the conscription crisis is infinitely more complicated than this oft-repeated analysis, but it still must not be ignored. Conscript, after all, was contemporary shorthand for Francophone, as the newspaper advertisement reproduced below makes clear. The Anglophone elite, politicians, and the media had not expended immense effort building the case that Quebec had not done its “duty” just to have inconvenient facts get in the way. It is this perception that colours the often dim view of conscripts in the historiography.

This attitude further helps explain why Canadian social memory venerates Vimy Ridge, an inconsequential skirmish when compared with the Hundred Days, above the battles from August-November 1918. But Vimy is about unity, a moment when Canadians came together to accomplish what the British and French could not. In contrast, thanks to the conscription crisis, everything from December 1917 on reveals divisions we would rather avoid.

This does not mean that conscripts did not fight effectively, but a failure to even perfunctorily examine, for instance, the recruiting situation in Quebec, fosters many contextual generalizations. The narrative also focuses solely on those who dutifully accepted compulsory service and reached the Western Front. Leaving aside conscripts who never left Canada, what about those who refused to “discharge their civil responsibilities as loyal citizens” (p. 11)? The Quebec City riots receive only a single mention (p. 56), accompanied by the blithe statement that “four civilians were killed.” It is worth emphasizing that these men were killed by Canadian soldiers; the four dead at Quebec City were surely the most reluctant warriors of all.

The focus on operations is further evident in the bibliography, which stretches to an impressive eleven pages, but is virtually devoid of French language sources. There is no mention of the recent pioneering analyses of Mourad Djebabla and Jean Martin, vital work that shatters long-held assumptions about French Canadian participation – and conscription – in the Great War.

Furthermore, conscription tells us a great deal about others whom contemporaries did not consider part of the national community. While we are introduced to individual examples of Métis, Black, and Japanese-Canadian conscripts, representatives of these communities are otherwise conspicuous by their absence (though immigrants, notably from Italy, Malta, and the Scandinavian countries, are prominent throughout). This is a missed opportunity to explore the wide gulf between the “white man’s war” of August 1914 and the German offensive of March 1918 – and how equality of sacrifice helped to alter Canada.

The operational claims also deserve closer scrutiny. In asserting conscript combat effectiveness, the narrative approaches Bishop Strachan territory, essentially arguing that all Canadian conscripts who reached the front lines became reliable soldiers. Surely some conscripts, like many volunteers, performed less than admirably, but there is no room for their stories here. Likewise, since conscript replacements were absorbed by existing volunteer battalions, it is difficult to assess what factors account for their general effectiveness. Certainly, since most conscripts never rose above the rank of private, the influence of their non-commissioned and junior officers – who just happened to be volunteers and combat veterans – probably did not hurt.

The work further tackles the claim that “Only 24,000 Conscripts Saw Service at the Front” (p. 225). This number, originally tabulated by GWL Nicholson’s Official History, is, by the work’s own admission, accurate, and one can only agree that this provided a significant reinforcement in frontline infantry strength during the Hundred Days. However, the use of “only” in conjunction with this number is surely appropriate in the overall context of the war.

Finally, in a comparison with the conscription crisis of the Second World War, and a related examination of what this tells us about the relevance of remembering conscripts today, Reluctant Warriors argues that Canadians paid a steep price for forgetting the operational importance of conscripts in 1918. On the contrary, in 1944-45, Canadians remembered that conscription fostered vicious internal division, a political context that always overshadowed the army’s need for reinforcements in Italy and Northwest Europe. It is hardly a surprise that the Canadian government did not seriously consider conscription during the Korean War, or any part of the Cold War, irrespective of the policies of our closest allies. The reader can further appraise the relevance of any suggestion that compulsory military service might again be utilized by Canada. Even in that unlikely event, one hopes that both the operational and the political lessons of the First World War will be carefully considered.

The real measure of Reluctant Warriors’ success will be how other historians assess the work’s findings. Ideally, they will incorporate the vital role played by conscript combatants into their assessments of the Hundred Days, while weighing the book’s other claims alongside critical recent publications such as Jean Martin’s Un siècle d’oubli: les Canadiens et la Première Guerre mondiale and Patrice Dutil and David Mackenzie’s Embattled Nation: Canada’s Wartime Election of 1917. While sidestepping crucial context, Reluctant Warriors is nevertheless a cri de coeur that demolishes old assumptions about conscripts in combat and provides an important contribution to the larger question of what Canada gained – and lost – in the First World War.

“Conscription 1917,” Canadian War Museum, accessed 26 February 2018, http://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/life-at-home-during-the-war/recruitment-and-conscription/conscription-1917/.

Sackville Post, 11 December 1917, p. 6; Saint Croix Courier, 13 December 1917, p. 7; Kings County Record, 14 December 1917, p. 3.

Mourad Djebabla, “‘Fight or Farm’: Canadian Farmers and the Dilemma of the War Effort in World War I (1914-1918),”Canadian Military Journal 13, no. 2 (Spring 2013), 57-67, http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vol13/no2/doc/Djebabla-Pages5767-eng.pdf

Jean Martin, “Francophone Enlistment in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1918: The Evidence,” Canadian Military History 25, no. 1 (2016), 1-16, http://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1824&context=cmh. Also, Jean Martin, Un siècle d’oubli: les Canadiens et la Première Guerre mondiale (1914-2014) (Outremont: Athéna, 2014) and Jean Martin, “La participation des francophones dans le Corps expéditionnaire canadien (1914-1919): il faut reviser à la hausse,” The Canadian Historical Review 96, no. 3 (September 2015), 405-423.

Andrew Theobald, Ph.D. is the author of The Bitter Harvest of War: New Brunswick and the Conscription Crisis of 1917, and is currently working as a researcher on 100 Days to Victory, a forthcoming documentary on the final battles of the First World War.