It took 12 years – and two years late – for Canada to reach the military spending threshold set by the transatlantic allies in September 2014. This represents a considerable change of direction since just last year, when former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau admitted that he had no intention of honouring Canada’s commitment to its allies. Unlike his predecessor, Prime Minister Carney is showing a readiness that may seem surprising. After all, just a few weeks ago, during the election campaign, Mr. Carney was only planning to reach the 2% threshold by 2030. What has happened since 28 April 2025?

It seems plausible that the acceleration in Canadian military spending can be explained by the pressure exerted by the Atlantic Alliance and the Trump Administration. At a time when a transatlantic consensus is emerging on a new target of 3.5% of GDP for military spending and a further 1.5% for related spending, it would have been difficult for Prime Minister Carney to defend a target of just 2%. A pattern seems to be emerging: a few days before a NATO summit, Canadian governments promise an increase in military spending with some annoyance. While Mr. Carney did not publicly comment on the relevance of NATO’s new targets, he took a swipe at NATO, declaring: “Our goal is to protect Canadians, not to satisfy NATO account.”

Yet Prime Minister Carney justified his haste with a severe assessment of the geostrategic environment. For him, American predominance is a thing of the past. “Now the United States is beginning to monetize its hegemony: Charging for access to its markets and reducing its relative contributions to our collective security.” As a result, Canada must reduce its dependence on the United States, he argued. To do this, almost half of the additional investments announced will go towards laying the foundations of an industrial defence strategy and diversifying defence partnerships outside the United States. Of course, the $4.1 billion or so announced for this purpose will not be enough to reduce the structural dependence of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) on the United States. But if Canada makes a commitment to its allies to reach the target of 3.5% of GDP in military spending by 2032 or 2035, the colossal sums that this would represent would make it possible to significantly reduce dependence on the US military industry. On condition that Canadian, European and Asian suppliers are given priority, and that the government invests in the capabilities needed for Canada’s strategic autonomy. After all, reaching 3.5% of GDP would be equivalent to $110 billion, or $47 billion a year more than is planned for 2025-26.

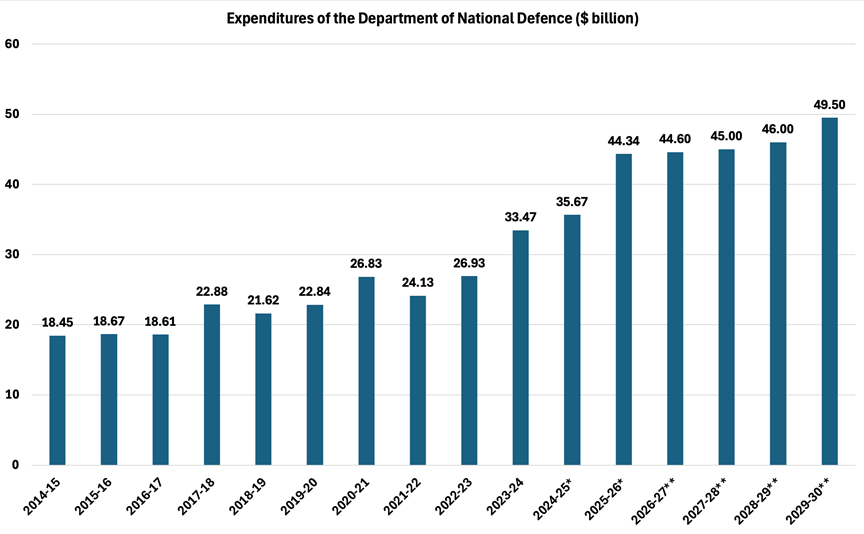

The increase announced by Prime Minister Carney is nevertheless considerable. For the Department of National Defence, it represents an annual budget increase of more than 24% on last year’s budget. This is an increase provided for by the vast recapitalisation programme of the CAF begun under the Trudeau government from 2017, but the effects of which have materialised especially since the large-scale invasion of Ukraine, as the following graph shows.[1]

Insofar as the increase for 2025-26 includes little capital expenditure, the Department should be able to spend the additional sums allocated. Investments in CAF salaries, infrastructure, Canadian industry and foreign partnerships should be easier to achieve in the time available. Capital expenditure, on the other hand, continues to experience delays and cost overruns.

In view of the many acquisitions planned over the next few years, however, the department will have to review its procedures in order to optimise its procurement strategy. It should not be the case that a so-called “urgent” requirement, such as the air defence and anti-drone capabilities for the CAF deployed in Latvia, which was budgeted for in 2022, was not operational until the spring of 2025. The new Defence Procurement Agency, once set up, will have to speed up the procurement process, establish closer partnerships with Canadian industry and support the latter both through long-term national contracts and on export markets so that it remains competitive.

The main risk to Canada’s military awakening is political fatigue. There is no guarantee that the current cross-party consensus on the need to increase military spending will hold, especially in a context where US threats could fade. Nor will Canadians accept endless increases in the budget deficit, and there is no indication that a majority would prefer higher taxes or cuts in social programmes in return for higher military spending. To justify the current rearmament of the CAF, the Canadian government will have to promote transparency and explain Canada’s military requirements in no uncertain terms. One of the best ways of doing this would be to emulate certain European allies, who disclose to their parliaments the NATO’s military capabilities targets set to implement the Alliance’s regional defence plans. If Canadians knew exactly what capabilities they needed to deal with the threats posed against their country, it would be easier to convince them of the sacrifices needed to invest in the defence of the country.

[1] The data for 2014-15 is actual expenditure incurred, that for 2024-25 and 2025-26 comes from the supplementary estimates, while future projections are taken from the expenditure forecasts in the new defence policy.

Justin Massie is a CDA Institute Fellow, professor and Head of the Department of political science at the Université du Québec à Montréal. He is also Co-director of the Network for Strategic Analysis, and Co-director of Le Rubicon.