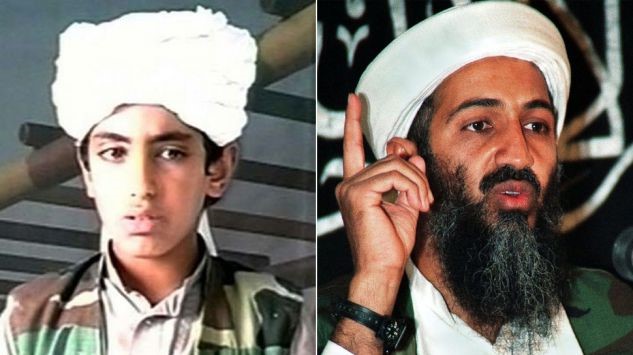

Two generations of bin Ladens. Photo: Daily Pakistan Global

Two generations of bin Ladens. Photo: Daily Pakistan Global

Aden Dur-e-Aden, CDA Institute Student Researcher discusses the potential for Al Qaeda/ISIS cooperation

In June this year, Canada extended its “advise and assist” mission in Iraq till March 2019. As a result, the number of Canadian soldiers forming part of the international coalition will increase, and the move is expected to cost more than $370 million. The International Coalition’s fight against ISIS is proving successful on the ground. The group has lost significant territory, and the flow of foreign fighters to Iraq and Syria has been reduced. Nevertheless, since terrorist groups continuously face pressures from both state and non-state rivals, they are good at adapting their structure and strategies to ensure their survival. Therefore, even with the encouraging news of ISIS’ defeat on the ground, Canada and its allies needs to be wary of equating this defeat with ultimate success against ISIS. Hence, in analyzing how ISIS itself may evolve from this defeat, it would be useful to focus on its often-ignored rival which can become an unlikely ally in the future, resulting in the strengthening of both groups.

Al Qaeda: neither down nor out

Although Al Qaeda is not dominating media headlines the way it used to during Osama Bin Laden’s reign, it is preparing a strong comeback. Two actions on its part support this conclusion: First, despite the weakness of Al Qaeda central in the Af-Pak region, its affiliates have continued to consolidate power in the regions where they can (e.g., Syria and Yemen). Second, while Zawahiri openly rebuked ISIS for its excessive violence and territorial ambitions, a new leader is emerging within Al Qaeda whose messages indicate that he is open to reconciliation with ISIS.

Hamza Bin Laden, Osama Bin Laden’s son, released six tapes between August 2015-May 2017 in which he refrained from critiquing ISIS, focused on the bigger narrative of US imperialism and its support for Arab governments, Palestine, cheered attacks on the west, and encouraged reconciliation between jihadi groups who are fighting each other in Iraq and Syria. In this way, he is cloaking himself in his father’s legacy, with the goal of attracting more people within Al Qaeda’s ranks. As has been discussed elsewhere, despite its differences with Al Qaeda today, ISIS has always praised Bin Laden, looking to establish itself as the true heir of his legacy.

However, if another Bin Laden takes the leadership of Al Qaeda and remolds the organization back to its founder’s vision, it will become more legitimate in the eyes of potential recruits who are now seeing ISIS lose on multiple fronts. Consequently, ISIS’ leadership may be encouraged to join forces with Al Qaeda, instead of risking irrelevancy in the jihadi marketplace.

What’s ideology got to do with it?

It is true that ISIS and Al Qaeda have several ideological differences, most prominently the targeting of Shia Muslims and the timing of the establishment of the caliphate. Scholars who study the two groups have noted this extensively. For example, in a recent Summer Academy organized by the Canadian Network for Research on Terrorism, Security and Society, researchers who study foreign fighter recruitment within ISIS noted the propensity of anti-Al Qaeda statements among ISIS fighters on Twitter.

Nevertheless, two developments within ISIS indicate the potential for marginalization of these disputes. First, as Ali Soufan notes, because of the territorial loss of ISIS’s caliphate, the ideological dispute between the two groups will fall away. Second, ISIS is not an ideologically united entity itself. Internally, it has faced criticism both from individuals who think that ISIS is not extreme enough, and those who think that it is too extreme. Therefore, in a recent document, ISIS asked its followers “to be content, accepting, and having good assumption of those in authority.” ISIS also stressed that ‘“it is improper to criticize the emir or “to insult, gossip, expose, provoke, or incite with the claim of reconciliation.”’

When Leaders L(i)ed:

In a recent research paper in the context of Myanmar, David Brenner analyzes the instances where insurgent leaders maintain or lose legitimacy among their followers. He concludes that if leaders can generate positive social identification towards the group for their followers, they can maintain their authority. In other words, followers need to know that the movement of which they are part of is doing something good and worthwhile.

Consequently, if the leadership of ISIS makes a strategic decision to join with Al Qaeda, they can generate positive social identification among their followers by portraying their actions as a struggle against common injustices faced by both groups. Combining this thought process with ISIS’s quashing of internal dissent, the merger between the two groups is not a farfetched possibility.

Available evidence suggests that it won’t be the first time that ISIS changed its original position. For example, in 2014, it portrayed itself as the group that brought the caliphate back; with the loss of territory, ISIS reframed those arguments and portrayed its defeat as a success because it was a test of their steadfastness from God. Similarly, because of its strict enforcement of gender roles, ISIS was unequivocally against women taking part in battle. Yet, recent evidence suggests that the group is increasingly using women as suicide bombers.

Terrorist leaders need to make continuous strategic and innovative moves to ensure their group’s survival. Therefore, if a territorially weak ISIS and a media stale Al Qaeda merge, a) they can share human and monetary resources instead of competing for them; b) they can present a united front and attract those recruits who might be disillusioned with their infighting; c) Al Qaeda can benefit from ISIS’s younger recruits and savvy media infrastructure, and ISIS can get the traditional street cred of the Al Qaeda brand under the auspices of another Bin Laden; Finally, d) they can both focus on enemies that are fighting them, whether regional or international state and non-state actors. It’s a win-win for both.

So, what can Canada do?

Canada can play a role in ensuring long term success against ISIS. Due to the nature of extremist groups, divisions and differences are bound to emerge among them, even if they form alliances for short or long term. One of the best defenses against such groups is to exploit those divisions. Therefore, in case ISIS moves towards a merger with Al Qaeda, instead of getting involved in complex theological arguments, Canada should focus on the ideological hypocrisy of these groups by highlighting the contrast in their own public statements against each other. These groups just don’t keep their own word. Thus, as opposed to merging and creating a hydra, the cynicism within their ranks will leave them worse off.