On April 14th the Liberal Party announced that, if re-elected, their government would establish a Defence Procurement Agency, replacing the much-criticized current business model that disperses accountability for the function among multiple cabinet ministers. The commitment is not new – the party’s 2019 election platform contained a similar promise that was never implemented.

Most Canadians do not care how the government organizes itself, they just want it to manage defence procurement effectively so that it delivers required outcomes for the Canadian Armed Forces and obtains appropriate value for taxpayers’ dollars. So, will a Defence Procurement Agency achieve that? The experience of other nations suggests maybe not.

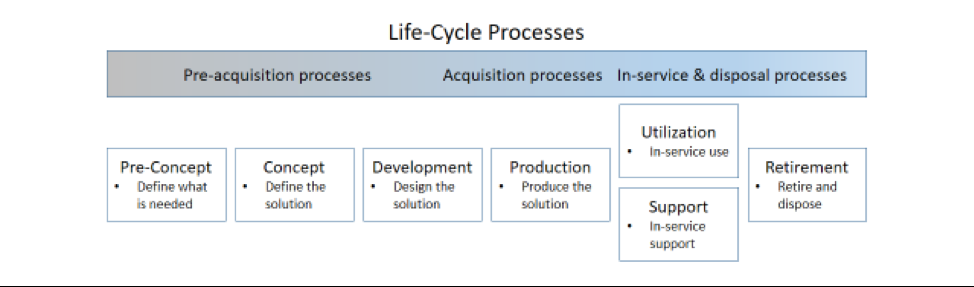

A number of Western nations that had separate procurement agencies – including the UK and Australia, both Westminster democracies like Canada – found that particular business model wanting and substantially restructured how they acquired equipment and supported their militaries. The NATO alliance itself went through a similar change. The NATO Support and Procurement Agency, the UK Defence Equipment & Support organization and Australia’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group all replaced separate acquisition and in-service support organizations with new integrated entities. These have an end-to-end life-cycle management framework for acquiring and sustaining defence equipment, and supporting military operations, based on internationally recognized best practices codified in the NATO Policy for Systems Life Cycle Management and its associated implementation guides, and ISO Standard 15288 System and Software Engineering – System Life Cycle Processes, upon which the NATO policy is built. The accompanying figure provides a high-level view of the processes described in these publications.

In this model, procurement is not treated as a stand-alone activity, rather it is considered integral to the entire business of capability acquisition and support. To be sure, like other specialized functions, procurement involves particular skill sets, business processes and controls, and this is provided for in the structure and governance of the organization. However, there is unified management of the totality of process from end-to-end.

This integrated approach, among other things, helps ensure that decisions are not based on a primarily short-term view. For example, what might be considered a good decision in an acquisition project to adopt a particular technical solution that enables a system to be delivered on time and on budget could be a bad decision from a full life-cycle perspective if another solution with higher up-front costs would have been significantly cheaper to operate and thus had a lower lifetime cost of ownership. A further benefit is that the integrated model better enables the establishment of a system-level performance management framework spanning the entire life-cycle of defence systems and capabilities.

The good news for Canada is that most elements of this kind of integrated organization already exist in forms that would facilitate bringing them together. Further, it would be an easier process than in many other countries because the more difficult aspects of their transitions have already been overcome here. Both the UK and Australia needed to strengthen integrated management among their separate military services and defence ministries, a problem Canada overcame starting in the late 1960s with Integration and Unification. Both those nations were also bringing together separate acquisition and in-service support organizations, each with their own cultures, but DND’s Materiel Group unified management of these functions (less contracting for procurement) in the 1990s. For its part, Public Services and Procurement Canada created a Defence and Marine Acquisitions Branch separate from its other government procurement business some years ago.

Simply bringing these two entities together under unified management would create a solid core of an organization mandated to provide end-to-end full life-cycle management of defence equipment and support to military operations. It would also not be very difficult to implement. Optimizing the new organization and its governance, business processes, IT systems and so on would take much longer, but in the end would be worth it.

There is, however, an important caveat: it is critical that this organization not reside outside the defence portfolio. Military personnel and equipment are inseparable components of defence capability, and fragmenting management of these would create a substantially more dysfunctional business model than the status quo and have a seriously disruptive impact on Canadian Armed Forces capabilities and operations. Political responsibility for it needs to be assigned to either the Minister of National Defence or (more likely, given the scope and scale of accountabilities) someone like an Associate Minister of National Defence for Acquisitions and Support. This minister can be assigned the legal authorities of the Defence Production Act (currently the purview of the Minister of Public Services and Procurement) by an Order-in-Council under the Public Service Rearrangement and Transfer of Duties Act. The current defence-related activities of Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada can also be handed over to the new minister as a simple administrative action, since Section 12 of the Defence Production Act already includes substantial legal powers in this area. The concept of a stand-alone defence procurement agency has been tried, found wanting and abandoned by a number of nations. On the other hand, the unified defence acquisition and support organization model is well-proven. It is therefore the lowest risk and best solution for Canada.