The Canadian Forces College plays a key role in preparing the CDS and his senior military team for national-level leadership. Photo: Canadian Press/Adrian Wyld

The Canadian Forces College plays a key role in preparing the CDS and his senior military team for national-level leadership. Photo: Canadian Press/Adrian Wyld

Twenty years ago, the Canadian government issued the “Report to the Prime Minister on the Leadership and Management of the Canadian Forces”. More commonly known as the “Young Report”, it called for sweeping changes to the professional education of Canadian military officers. As David Bercuson recounts, “the entire Canadian Forces (CF) at first crawled, then wandered, then stumbled, but eventually began to march forward with determination to a new professionalism rooted in the history and values of Canadian society, based upon a fighting ethos, with a democratic ethic and with one of the best-educated officer corps of any armed forces anywhere.” Since that time, CFC has quietly experienced a profound but unfinished educational revolution. To complete this, CFC deserves to be recognized as an organizational keystone through a renewed commitment by the CF to send not only its best and brightest students, but also directing staff as their mentors as well as an expansion of CFC’s academic faculty.

Since 1998, CFC has gone from a lone academic advisor to a fully-fledged Department of Defence Studies with 11 full time academics: the largest collection of professors exclusively devoted to the research and instruction of defence and security issues in Canada. Education does not get a lot of attention within the new Defence Policy, Strong, Secure, Engaged. However, the policy document does spend considerable space discussing the complexity of the strategic environment and points to a need for creativity and innovation in order to meet these challenges. Education, rather than training, is essential to policy development and implementation. To deliver officers prepared to deal with contemporary strategic reality, CFC needs to punch above its weight.

Training is the process that enables the generation of predictable responses to predictable stimuli. Militaries are comfortable with this model: training forms the basis of their professional development up to the point of mid-career whether in terms of tactical drills, piloting skills, seamanship, or the ever present demands of staff work. However, as the functional expert Major./Lieutenant Commander learns at CFC, military operations are about joining up the strengths and capabilities of multiple military services, each of which come with their own institutional histories, routines, language, and “styles” for how to accomplish a given task. All of this must be joined together in the operational plan to create a “unity of command”. At the Colonels/Captains(Navy) level, the strategic task becomes even more challenging with the integration of broad military effects with many government partners into overall national policy. Still higher, Generals/Admirals must work in international coalitions with fractious groupings of allies and international partners – all of whom bring their own caveats to the table – and more frequently, other non-state actors, corporations, and sometimes “frenemies”. At the highest level of complexity, “wicked” transnational security problems – computer hacking and viruses, weapons of mass destruction and terrorism, environmental degradation and global climate change, pandemics, natural and man-made disasters – all have the potential to disrupt national security even if Canada is not directly implicated in the events.

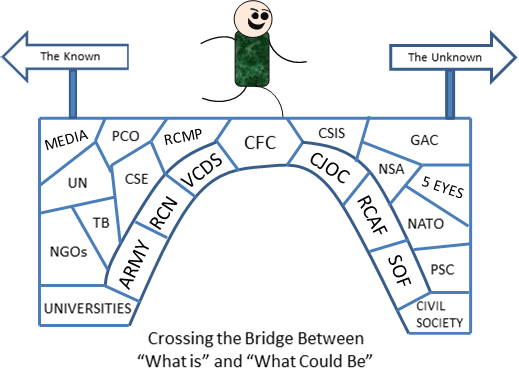

Diagram: Mitchell/With apologies to ‘Doctrine Man’ https://www.facebook.com/DoctrineMan/

Diagram: Mitchell/With apologies to ‘Doctrine Man’ https://www.facebook.com/DoctrineMan/

Training will not suffice in any of these circumstances. “Solutions” to these wicked problems simply do not exist. There are no professional knowledge foundations on which to base training for our students on what to do because the hows are so deeply contested amongst groupings of professionals. The military is already challenged by the multiple and often conflicting perspectives each of its partners bring to the table for framing what they consider the nature of the problem. What the military “knows” professionally is only one part, perhaps not even the most important part, in learning to appreciate and manage complex problems. For those tasked by increasingly vague guidance to “do something,” education rather than training will be necessary to understand how complex security challenges have evolved, how they affect institutional interests and people’s lives, why ongoing grievance drives violent actors to pursue their own drastic “solutions,” and whether situations can be nudged in more strategically positive directions.

Still, CFC is a very small organisation within a much larger defence bureaucracy, and one whose mission is frequently eclipsed by its educational partner, Royal Military College in Kingston. The “soft power” of RMC’s beautiful and historic limestone buildings, its photo-perfect red-coated cadets, and its huge alumni network dwarfs CFC’s ability to attract attention. In name recognition amongst Canadian academics, we are often confused for our Kingston colleagues. In their eyes, the arcane and esoteric nature of senior Professional Military Education (PME), with its emphasis on command and leadership, and the “operational planning process”, makes it difficult to explain CFC’s mission difficult to outsiders. While resembling a university in some of its forms (programmes, courses, credits, registrars, departments, professors, seminars, lectures, library, papers), CFC is not a university in function. It has a pragmatic and focused professional purpose which limits, to a degree, the free pursuit of knowledge: education must have concrete military and strategic utility to justify the human and capital expense of sending over 100 Major/Lieutenant Commanders and roughly 15 Colonel/Captains (Navy) away from their day to day responsibilities for 10 months, or the even scarcer public service executives.

Even within the military, CFC struggles with its “brand”. Tensions between academic study and professional development create rumours within the military that CFC’s academics have diluted the “warfighting” nature of its curriculum, or that CFC is a rogue institution which ignores the real professional demands of the military in a pointless quest for academic accreditation. In the most recent edition of the conservative Dorchester Review, these issues are actively debated from a variety of positions.

Despite CFC’s small footprint, its institutional effects ripple broadly, making it a strategic keystone for the CAF. Most of the senior officers in the military will eventually travel to Toronto for either the Joint Command and Staff Programme (JCSP) as Lieutenant Commanders/Majors, or the National Security Programme (NSP) as again more senior officers. Moreover, a growing number of senior public servants from security related departments are graduates of the NSP, renewing a professional “community of practice” in national security affairs within the Canadian government that has not existed since the closure of Kingston’s National Defence College in 1994.

Learn together to work together. Photo: DND/Sgt C Barber

Learn together to work together. Photo: DND/Sgt C Barber

By influencing the “software” of Canada’s senior officers and government officials, CFC shapes how officers and public servants create strategic and operational outcomes in the practice of their respective professions. Graduate level PME is a hybrid of a university graduate school programme and traditional staff college professional development, a discipline not offered by any other school in Canada. If time in Toronto is not to be wasted, ”ivory tower” academics have to reach both those in the field and at the conference table to ensure their educational journeys are professionally relevant. Those who need to be reached the most are often highly experienced officers and bureaucrats who have come to the conclusion that they already have all they need to navigate the treacherous waters of contemporary strategic affairs. CFC’s mission is not to teach its students how to do their job: they are already professional experts. Our mission is to help them think critically about their job, to more fully understand the larger political and strategic context in which they are embedded and the ways it influences how they act. Furthermore, officers have the rare opportunity to reflect on just how they think about their professional agency: is this the best way to achieve our mission? Are there other alternatives? In other words, to think outside of their professional boxes. This is particularly important in complex scenarios where small tactical actions can have enormous political consequences. Last, CFC seeks to develop articulate and critically expressive officers who can argue persuasively: to speak truth to power both convincingly yet diplomatically. These qualities make CFC a success; a keystone that illustrates the potential one small enterprise can have on much larger institutions. An architectural span may have many parts, but the keystone is the one which enables the whole structure to bear weight.

Fortunately, CFC is well on its way in helping military officers to cope with volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous environments. CFC exists to help officers cross the bridge from the professionally known into uncharted territory. By deepening and broadening their perspectives beyond the institution, officers come to realise they must learn about complex situations as they arise rather than resorting to increasingly irrelevant “by the book” techniques. In the future, the military will have to be profoundly creative, developing novel approaches. They will confront security challenges without immediate knowledge of the deeper historical or geographical context. Moreover, many problems they will confront will be unique to the political, social, economic, and environmental contexts which produced them in the first place.

Militaries will still need to be expert planners in running these operations, but they will also have to understand more – and do more: doctrine will never be enough. So, educated at CFC, these officers will become national assets for Canada, recognized for the excellence they bring to international coalitions and alliances. Indeed, our small military may itself become an international keystone. Our ability to contribute large material forces on overseas missions will always be limited, but the professionalism of our officers will make critical contributions given their collective intellectual capital.

But to achieve this outcome, the CAF has to grab the opportunity, in both academic and professional terms, to commit to developing this national asset. Strong, Secure, Engaged commits to strengthening Canada’s capabilities in pursuit of peace, security, and prosperity. A leveraged return on investment as promised in military personnel, platforms, and operational capacity will be enhanced through an equally strong commitment by ensuring that cutting edge education and research is available to an outstanding group of military officers, along with their public sector counterparts, as they prepare to assume their roles of leadership. Increasing the size of CFC’s academic faculty while transforming a College placement into a career-promoting period for directing staff would have a multiplier effect: bringing both of these talented groups together in the syndicate room generates deep and effective learning, as CFC has come to recognise. Delivering this future requires a modest investment in its personnel, both academic as well as military. The Department, and the CAF must firmly commit to sending their best and brightest, their most experienced senior officers to teach at CFC. Further, it must transcend any lingering doubts that this educational turn is in some way a danger to its own professionalism by committing sufficient resources to an academic expansion that will enable CFC’s professors to fully participate in every syndicate.

Although not yet seen to be so by all, CFC is already one of the most important schools of national security in this country and can only become more so in the future. Let’s give it the resources to do that job brilliantly.

Dr. Mitchell has taught professional military education not only at CFC, but also at the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre and the Singapore Command and Staff College.